Two Black Women Get Candid About Their Experiences on Accutane

Accutane, the most well-known brand name for the oral acne medication isotretinoin, is kind of like olives or jazz music. People either hate it or love it—there’s no in between. But issues with Accutane are a lot more serious than an aversion to briny flavors or syncopation: The drug comes with a rigorous process (specifically for people who can get pregnant) to even get approved for a prescription and a list of concerning potential side effects. On the flip side, those who successfully take the medication without any adverse reactions often report life-changing improvement to their skin.

But for Black patients who are curious about the drug, it can be hard to find client testimonials (positive or negative) from people with similar skin tones. That’s why we talked to Ryann Troutman and Alex Palmer, who’ve both used Accutane, about their skin-care journeys and experiences, as well as Houston-based dermatologist Tara Akunna, MD, founder of TaraMD, a telemedicine practice that makes culturally competent dermatological care more accessible for women of color.

Troutman, 24, was around 13 years old when she started having breakouts. At first they were “typical red pimples that would come to a head and then go away,” she tells Allure. But they progressed and became more cystic in her sophomore year of high school. Her mother, a pharmacist, had a negative experience when she took Accutane herself, so she urged her daughter to consider alternate solutions. Troutman tried everything from birth control to oral antibiotics to chemical peels and DIY apple cider vinegar rinses. She says birth control and the antibiotics did minimize her breakouts temporarily, but nothing worked long-term.

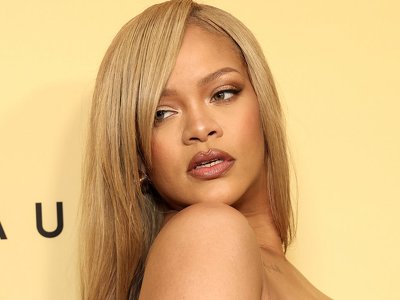

Ryann Troutman before starting Accutane.

Palmer, 28, had lived most of her life with fairly clear skin, described as “four or five pimples here and there around my period” and some hyperpigmentation. But in 2023, she went to a highly-rated licensed esthetician for a chemical peel. After that, her skin completely changed. “I had one area [of my face] where I was breaking out in pimples with the white puss in it, like normal pimples,” she tells Allure. “And all of a sudden, more started showing up, and more, and more, and more. And it just wouldn't stop.” She says that the breakouts covered her face, including her forehead, cheeks, jawline, nose, chin, and around her mouth. Palmer, who works as a nurse, said she doesn’t think it was an allergic reaction, or a fault of the esthetician given her popularity in the community and high customer rating. (To the esthetician’s knowledge, she has never had another client whose skin reacted like Palmer’s.) Similar to Troutman’s experience, Palmer’s friends warned her about the “extreme” side effects of Accutane, and at the time, she couldn’t find a lot of Black folks sharing their experiences with the medicine online. So, she too, turned to other remedies: facials, drinking green tea, vitamins, and Sculptra, a dermal filler that can treat acne scarring. Nothing worked.

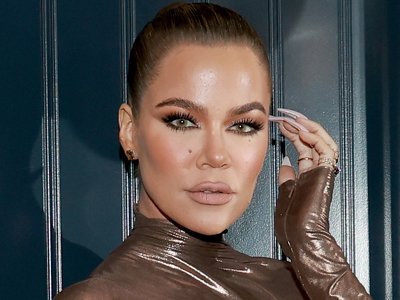

Alex Palmer before starting Accutane.

Black skepticism of Accutane, and the health care system in general, is not uncommon or unjustified. Dr. Akunna, who’s had patients raise concern when she introduces the pill in conversation, says that Black people are less likely to be prescribed Accutane, directly impacting the number of reviews available to prospective patients like Palmer. This gap in Black and white patients getting a prescription isn’t because it’s less effective for Black patients, Dr. Akunna tells us. It’s a result of barriers to access and challenges with the iPLEDGE system, a program that was put in place by the FDA to prevent pregnancy in patients on isotretinoin and prevent pregnant people from taking the drug. Ensuring you do not get pregnant is an important part of taking the medication, because isotretinoin can cause birth defects, premature birth, and even fetus termination, but there have been complains that this program—which requires patients who can get pregnant to take monthly pregnancy tests at their doctor’s office before they can get a refill and use two forms of birth control or remain abstinent throughout their treatment—creates barriers to accessing the drug. The doctor says that iPLEDGE has been “shown to disproportionately delay or interrupt Accutane courses for non-white patients,” primarily due to technical issues with the website or missing appointments or pick-up windows for the drug.

She adds that there’s often a difference in how doctors prescribe the medication to white versus non-white patients, noting a disconnect between the two parties on what’s a valid and non-valid reason to start Accutane. In Dr. Akunna's experience, white patients who go on Accutane are typically seeking acne treatment, but that's not always the case for Black patients. “We know that when our [Black] patients come in, sometimes they're not even bothered by their acne. They’re really concerned about the hyperpigmentation,” she says, a potential side effect of having acne that Accutane can also help treat. “For some providers, maybe they think hyperpigmentation is not a big deal. But to us, it is a big deal.” As a Black dermatologist, Dr. Akunna says she’s aware of how hyperpigmentation affects our perception of ourselves and the way we’re perceived in the world. “Some providers will minimize or downplay hyperpigmentation, and thus, are less likely to treat it as a medical condition/concern,” she says. “I have a lower threshold, as I’m taking into consideration the effects of hyperpigmentation in addition to the acne when evaluating patients.”

Tired of failed attempts to achieve clearer skin, both Troutman and Palmer, 22 and 27, respectively, at the time, turned to Accutane. Derived from vitamin A, Dr. Akunna tells us that the drug is a prescription pill that shrinks oil glands, reducing the production of the oil that causes acne. “A lot of people think it's like some random chemical…, but it's just essentially [really high doses of] vitamin A,” she tells us. (Retinol is another form of vitamin A commonly used to treat acne.) Before getting approved for the prescription, Troutman and Palmer had to enroll in iPLEDGE, which includes having to have two negative pregnancy tests 30 days apart before getting the prescription. Patients who can’t get pregnant generally have a much quicker and simpler process to access the medication because there are no associated pregnancy risks.

Troutman and Palmer also had to take a pregnancy test once a month for the time they were on the drug; if you do become pregnant while on the drug, Dr. Akunna says, you must immediately stop taking the medication and report the pregnancy to iPLEDGE. After, you’ll be referred to an obstetrician to evaluate the risk of fetal exposure and advise on the best path forward. Palmer adds that she had to take monthly quizzes with questions about what to do if you get pregnant or if a neighbor offers you their Accutane pills, something Dr. Akunna confirms is standard.

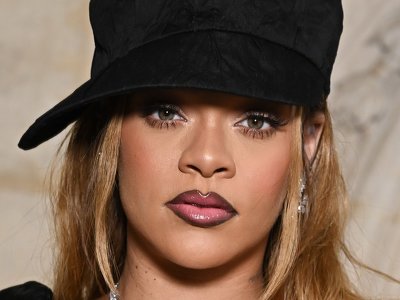

Palmer after one month on Accutane.

Palmer after four months on Accutane.

During the first month on the prescription, the doctor says that patients may notice frequent breakouts as the skin purges and cells turn over. By month two or three, though, they should notice fewer breakouts. Palmer, however, skipped the purge stage and saw significant improvement within two weeks. “I know some people online were saying, ‘It gets worse before it gets better,’” she says. “I was already worse—that's what I think. It just got better immediately.” She did experience skin dryness, a common side effect, and sunburn, admitting that she believed the myth that Black people didn’t need sunscreen. (She’s since started using sun protection.) Other more severe potential side effects, like depression and suicidal thoughts, were never an issue for the nurse. On the contrary, she recalls feeling much better about herself than she had since the breakout.

Troutman saw progress in her skin around the two month mark, but experienced the expected dryness like Palmer in the beginning. She remembers her nose being especially dry, and seeing a small amount of blood on the tissue whenever she’d blow it. Towards the end of her nearly eight-month course on the pill, Troutman got intense brain fog. (Dr. Akunna says that research does not show a significant increase in neuropsychiatric side effects for patients taking Accutane, but doctors do monitor for any mood changes.) “It was the final [exams] season, and I noticed that it was really hard for me to focus,” Troutman says.

Troutman after Accutane.

Her mother encouraged her to see a doctor, so she went to her university’s student health center. She intentionally sought out a Black health care provider, with whom she says she had a very positive experience. The school doctor conducted blood work and discovered that Troutman’s liver levels were elevated. She was also quite concerned to learn that the dermatologist hadn’t done any blood work prior to or during Troutman’s medication cycle. In fact, when Troutman had asked her prescribing dermatologist if it was necessary to do bloodwork in her consultation appointment, as she’d researched prior to the visit that it was standard practice, the doctor told her, “that practice was a little ‘old school’ and wouldn’t be necessary.” Dr. Akunna disagrees, saying that Accutane can cause elevated liver enzymes, “which is why we check labs prior to and during treatment.” A blood test, which is recommended by Accutane's manufacturer, before a patient starts the prescription will reveal things like high lipids and liver conditions. In those instances, Dr. Akunna says treatment steps forward are determined on a case by case basis, dependent on lab results and the condition of the patient’s liver. Dr. Akunna also runs another blood test at her patients’ peak dose, which is recommended by the American Academy of Dermatology to detect any abnormalities.

Tro

- Last

- April, 28

-

- April, 27

-

- April, 26

-

-

- April, 25

-

- April, 22

-

-

-

-

- April, 16

-

-

-

-

-

- April, 15

-

-

-

- April, 13

-

-

News by day

5 of July 2025